Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Special Offer from PM Press

Now more than ever there is a vital need for radical ideas. In the four years since its founding - and on a mere shoestring - PM Press has risen to the formidable challenge of publishing and distributing knowledge and entertainment for the struggles ahead. With over 200 releases to date, they have published an impressive and stimulating array of literature, art, music, politics, and culture.

PM Press is offering readers of Left Turn a 10% discount on every purchase. In addition, they'll donate 10% of each purchase back to Left Turn to support the crucial voices of independent journalism. Simply enter the coupon code: Left Turn when shopping online or mention it when ordering by phone or email.

Click here for their online catalog.

Another Father is Possible

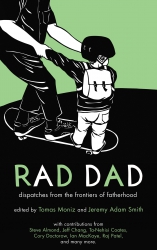

A REVIEW OF RAD DAD: DISPATCHES FROM THE FRONTIERS OF FATHERHOOD

A REVIEW OF RAD DAD: DISPATCHES FROM THE FRONTIERS OF FATHERHOOD

EDITED BY TOMAS MONIZ AND JEREMY ADAM SMITH

PM Press, 2011

“The other day someone asked why I keep doing Rad Dad even though my kids are teenagers. I smiled and said, 'I do it because I'm a father, and I know I'm a better father when I have community…'” - Tomas Moniz, co-editor, with Jeremy Adam Smith, of Rad Dad: Dispatches from the Frontiers of Fatherhood.

When I was asked to write a review of Rad Dad, I was like, “Oh yeah, I love that book!” Oddly that love has made this a real challenge. Over the last four weeks of fits and starts I began having the sinking feeling that I was not nearly rad enough of a dad to do the book justice. For a variety of reasons, mostly related to my son’s adoption but then I suppose to habit, I stopped going to protests in 2007. I really stopped being any kind of organizer a year and half later when I moved to Houston with my wife. And though I recently got refocused on organizing, my work has been submerged under a barrage of institutional crises that are far from exciting. At the same time, the Occupy movement has taken off across the country. And though it reached Houston a couple of week ago, surgery and the new job (ironically) have mostly kept me away from the parks and stuck in the house.

At some point, however, what all of this has made me realize is that the key theme of the book, as I understand it, is that we all need a community of support to realize a vision of parenting which actually manifests that other, better world we’ve all been working toward for so long. In other words, the “rad” part has little to do with protests. The family is a microcosm for society, and the confluence of race, class, and gendered hierarchies flow right through it, often in the person of the father. It would be simplistic to say that challenging these hierarchies as they enter the household is the key to a revolutionary movement. On the other hand, it is hard to imagine a successful revolutionary transformation that doesn’t include a radical redefinition of parenting, and fatherhood in particular.

And so whatever else Rad Dad has to say (and there is a lot here), I think it is clearly a call to fathers to get it together, literally, and start talking about the privileges we assume in the household and in the world. Then start to dismantle those privileges in favor of that deep sense of democratic practice that motivates movements like Occupy Wall Street, at least at their best moments. The women’s movement challenged us to redefine our understanding of public and private—not as competing spaces, but as mutually reinforcing spaces. In a way, Rad Dad breaks down that barrier for activists.

Funny and moving

Now that I have presented a really heavy agenda for the book, I should say that it is often funny, always moving (I cried several times reading it), and constantly thought-provoking. There is no ten point platform here for effective radical fathering—and certainly no “radicaler-than-thou” kind of line. It is full of personal stories of fathers figuring out what it all means. Sometimes failing, sometimes succeeding, but always finding that once you’ve determined parenting to be an intentional activity that challenges the conveniences, trends, and identities embedded in the dominant culture—it's really fucking hard.

There is the blatant consumerism that surrounds us and that we all take part in, even as we push back against the worst of it and try to live outside the “juice box.” There is also the ever-present militarism that seems integral to the development of gendered understandings of maleness in this society. It’s so prevalent that many dads who make extraordinary efforts to keep the celebration of violence and war out of the home find their sons pretending to shoot their friends and neighbors anyway. Then there is the constant discovery that even the most pro-feminist dads among us still exert power in our relationships or assume privileges that derive from gendered hierarchies.

All of these struggles are discussed directly and also serve as a backdrop for personal narratives. It is impossible not to find yourself as a dad here, having made the same efforts and the same mistakes. The conversation that results is an important one. You discover you are not alone in the “failures” and that there are ways to navigate through them if you are willing to talk about it. Even the first chapter of the book, Keith Hennessy’s “Notes from a Sperm Donor,” which launches the conversation with a fascinating self-exploration of being a father but not a parent, raises interesting questions about what it means to even want to be a father to begin with. What is behind the desire to reproduce ourselves?

One of the great things about Rad Dad is how the collection gives voice to some of the concerns of fathers facing all of the above, plus additional hurdles. Sean Taylor’s discussion of confronting racism in a visit to a park to play with his daughter is one of the most powerful stories in the book. Racism and identity politics are present throughout Rad Dad, but Sean’s narrative forces a direct confrontation with the reality of racism in a way that is unique in the volume.

Burke Stansbury’s discussion of the challenges he and his partner confront parenting a medically fragile child with an extreme muscular disorder raises many issues both personal (navigating the distance between his expectations of being a father and how things have unfolded) and systemic (serious problems of access in our healthcare system). Jack Amoureux talks about raising his child as a transgendered father and how this intersects with moving in social and professional life beyond a dichotomous notion of gender. If there is a second volume, I’d love to see more of these stories.

Leave no one behind

The book is rounded out by a section of thematic essays on “The Politics of Parenting” built around personal narratives that primarily feature the editors Tomas Moniz and Jeremy Adam Smith. Tomas Moniz’s “A Kid Friendly Wild Rumpus” is particularly timely:

People have embraced the mythology of the revolutionaries and activists who left their families behind, so total was their commitment. But how about a new mythology, one that celebrates revolutionaries who refuse to leave anyone behind and refuse to remain silent.

I was just finishing the book the weekend Occupy Wall Street began. At the time the action itself seemed very far removed from my concerns as a father, even if the issues of economic inequality and poverty are inherently family issues. Indeed, it seemed the only way for me to participate (and I was certainly interested) was to leave the family behind. Since then it has been fascinating to watch some of the occupations incorporating a variety of “kid friendly” or family friendly activities. Parallel teach-ins focused on families; numerous Halloween activities, sleepovers, and art classes have become features of the movement. It is obvious that this was not part of the original “occupation plan” but that parents have created spaces to be included as parents—refusing to “leave anyone behind” and refusing to “remain silent.”

This third section ends with a clarion call from Tata to “Wake Up, Dads!” and fight for a society that truly acknowledges and appreciates parents—while making it possible for more of us to play that role at home with our children. The volume concludes with a great collection of interviews with “rad dads” like Ian Mackaye, Jeff Chang, Raj Patel, Steve Almond, and Ta-Nehisi Coates.

So, I would encourage anyone to read this, dad or not. But for the dads there is real value here, a richness of explorations about the challenges of fatherhood that is unique in my experience. Jeremy Adam Smith writes in one of his essays, ending a passage about how his commitment to feminist ideals was challenged by becoming a parent:

There are alternatives; you don’t have to be the man your father was; you don’t have to be the idiots we see on TV; you can be a new kind of man, and you can help your sons become that kind of man.

I can think of no better aspiration, indeed a more radical agenda, for fathers. And we are going to need each other to do it. So, dads, let’s get started!

Tom Ricker lives in Houston and is the proud father of Benjamin Won-bin Dennis Ricker. He has been an organizer in social justice and solidarity circles since 1995 and is currently the director of the Quixote Center. Also a musician and writer, in December 2011 he will release (with Austin based producer David Wilson) the CD Wünderland under the band name Minivan Gogh. He can be reached at ricker.tom (at) gmail.com.