Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Special Offer from PM Press

Now more than ever there is a vital need for radical ideas. In the four years since its founding - and on a mere shoestring - PM Press has risen to the formidable challenge of publishing and distributing knowledge and entertainment for the struggles ahead. With over 200 releases to date, they have published an impressive and stimulating array of literature, art, music, politics, and culture.

PM Press is offering readers of Left Turn a 10% discount on every purchase. In addition, they'll donate 10% of each purchase back to Left Turn to support the crucial voices of independent journalism. Simply enter the coupon code: Left Turn when shopping online or mention it when ordering by phone or email.

Click here for their online catalog.

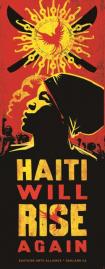

Haiti and the Human Made Disaster

On January 12, 2010 Haiti was rocked by a massive (MMS 7.0) earthquake. The epicenter of the earthquake was not far from some of the major population centers of Haiti, including the capital, Port-au-Prince and the city of Jacmel. As of January 28, the confirmed death toll is 170,000, though that number is expected to continue to rise.

On January 12, 2010 Haiti was rocked by a massive (MMS 7.0) earthquake. The epicenter of the earthquake was not far from some of the major population centers of Haiti, including the capital, Port-au-Prince and the city of Jacmel. As of January 28, the confirmed death toll is 170,000, though that number is expected to continue to rise.

The current outpouring of support for those who survived the earthquake and now find themselves without shelter, food or clean water is much needed. It is worth bearing in mind, however, that the January earthquake is the latest in a long list of disasters that have marred Haiti’s history, most of them caused by human activity as opposed to natural forces. For those of us in the US it’s also worth paying attention to the bigger picture of suffering in Haiti, as our government—and by extension all of us—have been its primary cause.

In the seventeenth century, Haiti was among the most prized possessions of the European colonialists, who used the fertile land for growing sugar cane and manufacturing sugar, molasses and rum. Sugar refining is a rushed process, as sugar cane juice will go rancid within a day or two. Slaves brought from Africa spent hours stoking furnaces and stirring vats of boiling liquid often long into the night and often suffering from serious burns. Once a slave took up the work in the sugar fields, he or she was not expected to live more than eight to ten years.

In the shadow of this brutality, Haitian slaves took up arms against their European masters. The Haitian revolution began in 1791 and culminated in the declaration of Independence in 1804. Haiti became the first slave colony to successfully cast off the yoke of its masters. Unfortunately, though a free country, Haiti has never really been liberated from the colonial powers. In 1825 Haiti agreed to pay massive reparations to French slave holders, essentially paying reparations for their bodies. This set Haiti on a path of near permanent debt—beholden to international financial institutions.

Colonial economy

As a result of Haiti’s massive debt burden and periodic US military intervention, industrialization never really got off the ground in Haiti. In 1990, 186 years after independence, Haiti still functioned as a colonial economy. Haiti provided cheap raw materials—coffee and cocoa now largely taking the place of sugar cane—for processing into finished goods outside the country. As other countries in the Caribbean, West Africa and Asia were growing exactly the same crops, the supply of cheap coffee and cocoa soon outpaced demand, and world commodity prices dropped. The collapse of the global commodities market coupled with austere fiscal policies imposed on the Haitian government by the World Bank and IMF ensured that Haiti’s economy never got off the ground. Meanwhile, the human toll of these policies could be seen not only in staggeringly high poverty rates, but also in high illiteracy rates, lack of food security and lack of basic medical facilities.

Politically, by 1990 Haitians had lived under many years of dictatorship. François Duvalier (Papa Doc) and his son Jean-Claude Duvalier (Baby Doc), dictators who ruled successively from 1951 to 1986 were both supported by the United States, and favored economic policies dictated by Washington over those that may benefit the Haitian people. When the population resisted, they were met with a brutality reminiscent of the French wars against the eighteenth century slave revolt.

By the end of the dictatorship of Baby Doc in 1986 Haiti could be considered a failed state in many respects. But in 1990, something startling happened. Despite years of living under the heels of dictators and at the whims of global financial policy, impoverished communities in Haiti organized their own candidate to take part in the first free Presidential elections in generations. That candidate, Jean Bertrand Aristide, won those elections to the great shock of many, including those who had polled public opinion before the election took place. Yet again, the Haitian people would pay for their streak of independence and have been perhaps paying a price for the crime of electing a popular candidate ever since the election of Aristide.

In 1991 the United States was instrumental in the process that ended Aristide’s first term as president after some seven months in office. When the Organization of American States announced that it would begin an embargo of Haiti in protest of the illegality of Aristide’s removal, the first Bush administration announced openly their intent to violate any embargo. Three years later, Aristide was restored to power but only under fiscal austerity conditions which made it impossible for him to fulfill the promises made during his election campaign.

Political turmoil

Since that time, Haiti has been in a near chronic state of political turmoil, with Aristide and his allies in power but largely unable to change basic economic realities in Haiti. For example, under Aristide, many people lost access to electricity and water while cheap imported goods cut out local production. In 2004 there was yet another US Government-supported coup d’etat against Aristide, which disposed him from power and forced him into exile.

From an economic point of view, Haiti’s needs are fairly clear assuming that it, like every other country, must work within the global capitalist framework. Like much of the “developing world” Haiti must find a way to move away from being an exporter of cheap raw materials and towards exporting higher value finished goods while simultaneously undertaking policies to develop a middle class within Haiti. These policies are not rocket science—indeed nearly every developed country has followed a similar path—but in order to undertake them, Haiti must first overcome barriers to its political sovereignty and barriers to its democracy. While these policies are in the best interest of the Haitian people, they are not in the best interest of those who currently formulate US policy. US planners continue to see moves towards a more independent Haiti as deeply problematic insofar as Haiti represents the “threat of a good example.” Just as the US feared a free and independent slave colony so to does it fear an economically free and stable Haiti.

Recent signs from the IMF and its de facto ruling body, the Group of Seven richest countries, indicating that Haiti’s remaining international debt will be cancelled in the wake of this earthquake are encouraging. Debt cancellation can provide some fiscal space to support things like paying wages to nurses and schoolteachers as opposed to repaying debts that have already been paid in blood and in money. Whether or not debt cancellation also leads to the creation of political space to follow a course independent of the whims of Washington is an open question.

Haiti itself is a small country, but should it be successful in overthrowing US imperial pursuits it would be part of a wave of independence that stretches back to the Cuban revolution of 1961. More recently, much of South America has openly declared hostility to the history of US aggression in the region with nearly all governments at least espousing populist rhetoric over kowtowing to the US superpower. Whether or not the fire of independence is allowed to spread to Haiti and its Caribbean neighbors will depend largely upon the state of social movements in the US.

Should those movements fail, the recent earthquake may simply be the latest in the long list of Haiti’s disasters, as opposed to the last.

Sameer Dossani has been an activist on issues of global economic justice for fifteen years. Former Director of the 50 Years is Enough Network, Sameer now heads the Demand Dignity campaign for Amnesty International, USA. (Opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of Amnesty International.)