Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Special Offer from PM Press

Now more than ever there is a vital need for radical ideas. In the four years since its founding - and on a mere shoestring - PM Press has risen to the formidable challenge of publishing and distributing knowledge and entertainment for the struggles ahead. With over 200 releases to date, they have published an impressive and stimulating array of literature, art, music, politics, and culture.

PM Press is offering readers of Left Turn a 10% discount on every purchase. In addition, they'll donate 10% of each purchase back to Left Turn to support the crucial voices of independent journalism. Simply enter the coupon code: Left Turn when shopping online or mention it when ordering by phone or email.

Click here for their online catalog.

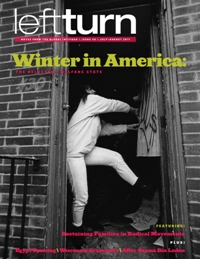

The Reluctant Welfare State

Social welfare programs are easy fodder for budget debates. A mere 18 percent of the federal budget is earmarked for discretionary spending, which includes welfare programs like public housing, food stamps, and cash assistance. Yet to hear foes spin it, one might think that social welfare programs comprise the bulk of the US budget and are responsible for sinking the country into unimaginable debt.

Social welfare programs are easy fodder for budget debates. A mere 18 percent of the federal budget is earmarked for discretionary spending, which includes welfare programs like public housing, food stamps, and cash assistance. Yet to hear foes spin it, one might think that social welfare programs comprise the bulk of the US budget and are responsible for sinking the country into unimaginable debt.

To close the fiscal year gap and keep the government running for the rest of fiscal year 2011, Republicans recently took aim at discretionary spending with the Welfare Reform Act of 2011. When the dust settled, the cuts to social services—though less than they would have been due to the quick action of activists, advocates, and some elected officials—were stark. (See sidebar for outline of recent cuts.) These cuts are beginning to play across the country as cash-strapped cities and states have fewer funds from the federal government to use to deliver services.

Sheila Collins works for the city of Spokane, Washington. Spokane, a mid-sized city surrounded by rural country, acts as a hub of services for a large region. “Our Community Block Grant was cut by 16 percent,” Collins stated. “That’s money that would have gone directly to neighborhoods for housing and social service programs.”

Collins went on to specify the consequences of these cuts: “Some people will get dropped from services with no more than a month’s notice. Some of these will be people with the most need for physical and mental health services. Some will end up living under bridges, turn up on emergency room doorsteps for routine care, or wind up in jails, which are more and more serving as our mental health institutions.”

Noting that the recent cuts are only the beginning, Collins predicted that “in the struggle to set the 2012 federal budget, the cuts will be even starker.” The fiscal year 2012 budget that Republican Representative Paul Ryan champions is what Collins calls an “all-cuts budget,” one that proposes no new revenue sources—notably , no new taxes.

“This budget is being balanced on the backs of the poor and vulnerable,” said Collins.

It is common for politicians to use taxes as an issue to leverage support for policies hostile to social welfare programs. “Programs for the poor are always under more severe attack during tough economic times,” writes Premilla Nadasen, history professor at Queens College of the City University of New York, in her book Welfare Warriors. “There is always this tension between taxes and aid to the poor. Social welfare policy funding issues always get framed in terms of budgetary constraints.”

History of scapegoating

Buried in the rhetoric of the budget debate is a long history in the US of attributing poverty to unwillingness to work. A recent example occurred in Congressman Paul Ryan’s official Republican response to Obama’s 2011 State of the Union address in which he warned against a future that “will transform our social safety net into a hammock, which lulls able-bodied people into lives of complacency and dependency.”

Much of the US welfare policy is rooted in Elizabethan Poor Laws, which Protestant reformers brought with them from England to the North American colonies. These laws chastised the poor for having personal failings that led to their poverty. Hard work was supposed to be the cure, and those who did not work or seek to work did not deserve to receive help. Nadasen notes that “largely throughout US welfare policy history, there has been a distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor.”

Prior to the 1930s, the US welfare state virtually did not exist. What little relief for the poor there was came from private, often religious, charity organizations. When the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression left thousands in the working and middle classes unemployed and destitute, however, the government discovered the need for federally coordinated and funded relief.

President Franklin Roosevelt’s response to the Great Depression was the New Deal, which focused on putting people back to work. But in addition to instituting work programs, the New Deal created one of the most important pieces of social welfare legislation in US history, the Social Security Act of 1935. Mandatory for all workers and self-funded through taxes, the Act guaranteed the elderly an income—a revolutionary idea in the history of US social welfare.

Included in the original Social Security Act was Aid to Dependent Children (ADC), which provided cash assistance to households headed by women, primarily widows. While Social Security grew to be a much-loved, fiercely protected social insurance program, ADC fell into disrepute over the years as hardened views on poverty, work, and personal responsibility mixed with racism and sexism.

Reforming public welfare

In 1967, an effort to reform ADC (now known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children or AFDC) was mounted in Congress. As the number of women receiving AFDC increased, so, too, did the resentment aimed at them, despite the fact that most of the women held jobs. “The vast majority of those who use aid programs are in the work force,” notes Nadasen, “paying taxes like everyone else. It is a small minority of people who rely on public services regularly over a long period of time.”

In the 1960s and 1970s conservative forces in Congress wanted reform that would reduce the number of women on the AFDC rolls by introducing stricter work requirements. By this time 40 to 45 percent of women receiving AFDC were black, and increasing numbers of them had never been married. “There was a real parallel between the changing face of the welfare rolls and a move toward a very punitive system that aimed to move people to independence,” says Nadasen..

In 1980 Ronald Reagan launched a full assault on public assistance programs. Revenue lost to Reagan’s tax cuts eliminated 57 social programs, AFDC was cut by over 17 percent, and one million people lost eligibility for food stamps. The cuts also focused on mental and public health assistance and Medicaid. In many ways the US has yet to recover from these brutal social welfare policies.

In 1996, under the presidency of Bill Clinton, the US undertook another large reform of AFDC. Clinton’s goal was to “end welfare as we know it.” The name of the act, the Personal Responsibility and Works Opportunity Act of 1996, said it all. Racism and sexism played prominently in the debate, with the image of the “welfare queen” held up for public ridicule.

Clinton proposed reducing the welfare rolls by a third with the introduction of yet more stringent work requirements. Limits were imposed on the lifetime benefits a person could receive. Perhaps most detrimental of all, however, was ending AFDC status as an entitlement program, moving it from mandatory funding to discretionary spending. Now Congress must periodically reauthorize funding levels to AFDC, whose new name is Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF).

Throughout the years, reforms to social welfare in the US have focused the blame for poverty on those who receive assistance rather than on the systemic issues that lead to and perpetuate poverty. “The debate today is a repeat of a lot of the 1970s and 1980s in many respects—it's about race and taxes,” Nadasen states. “But now we are not just seeing attacks on aid to the poor, but attacks on education and Medicare too. These are core middle class entitlement programs.”

Social welfare programs have not fared well under either party, Republican or Democrat. Indeed, public welfare programs often fare worse under Democrats. “The Left hasn’t dealt very adequately with aid to the poor and welfare in general,” argues Nadasen. This does not only apply to the liberal left in the US. Balancing the effects of capitalism and racism on poverty with the need to advocate for more robust government services to the poor may not be comfortable for many of those on the radical left. Perhaps frustratingly, however, it remains that local, state, and federal governments are presently best equipped to deliver coordinated aid to the poor.

The moral and political outrage that has emerged around the cuts to social spending is genuine. Religious leaders began fasting, Washington, DC Mayor Vincent Gray got himself arrested in protest, journalists on the left exposed the true cost of the cuts on the economy, and academics debunked Republican claims that cuts to social spending would balance the budget.

Absent from the public discourse, however, was an organized voice of the very people who rely on welfare programs. “In the past, people living on welfare have organized to defend benefits. We can’t forget that,” says Nadasen. In the months to come as the budget for 2012 is fought over, these voices will need to become vital to the organizing if we want to effectively protect spending for public welfare programs.

Morrigan Phillips is an editor at Left Turn and lives in Boston, where she works as a community social worker.